The History of Japanese Art

Unlike most societies that thrive on the mainland, which have the benefit of a mix of cultures and knowledge from nations that came before, Japan remained an isolated island for most of its existence, apart from two distinctive waves of influence from the outside world.

The first was the introduction of Buddhism from mainland Asia to Japan, and the second and most significant change was in 1868 when the Meiji government ended the national isolation imposed on the country by the feudal rulers, the Shōguns, and allowed a new wave of modernisation and westernisation to take place.

The history of Japan and, therefore, Japanese art are both very interesting and unique. From the ancient Jōmon times to the pre-war Meiji period, the history of Japanese art has many facets.

Jōmon Art

The first known settlers in Japan were the Jōmon people, who lived there from 10,500 to 300 BCE. The Jōmon people were nomadic hunter-gatherers who eventually established small settlements comprising wooden and thatch huts. They gained their name from the cord design that decorated the surfaces of their clay posts, for which they are very famous.

The Jōmon people made decorated clay storage vessels, clay figurines, and crystal jewellery. Over the years, as they began to settle in small villages, the Jōmon people had more time on their hands to produce beautiful ceramics, which they decorated with bamboo. The ceramics produced later in the Jōmon period were much more expertly designed than the earlier ones made when the people were still nomads.

Alongside clay and ceramic vessels, the Jōmon people were also famous for their clay figurines known as Dogū. These earthenware figurines were made all across Japan except Okinawa and were humanoid with big eyes, small waists, and wide hips. These figurines form part of a belief that existed before the spread of Buddhism to Japan, and there are a few theories regarding their use.

While some scholars believe that each person had a figurine and they were probably used in some form of sympathetic magic, similar to worry dolls, others claim that since most of the dolls appear to resemble females and have large abdomens indicating pregnancy, the Dogū were mother goddesses used to enhance fertility.

Yayoi Art

Around 300 BCE, another wave of immigrants came from mainland Asia to Japan, bringing with them their knowledge of wetland rice cultivation and the manufacture of copper weapons and bronze bells.

The Yayoi people also knew how to make wheel-thrown, kiln-fired ceramics, which were a change from the ceramic vessels made by the Jōmon people.

The introduction of rice cultivation was a great asset to the inhabitants of Japan as the Jōmon moved from their mountain villages due to the cold weather, to the coastal areas where they relied on fish for food. There was a vast increase in the number of vessels produced by the Jōmon people to store their fish. Archaeological evidence suggests that the production of clay pots and ceramics largely increased towards the end of the Jōmon period before the arrival of the Yayoi.

Kofun Art

Either due to internal developments or foreign influences, the third stage of Japanese prehistory, known as the Kofun period of 300 - 710 AD, brought interesting changes regarding art.

Elaborate tombs began to be made, first smaller ones on hilltops, then larger ones on flat land. The tombs were characteristically shaped as keyholes, and clay sculptures known as Haniwa were placed at the entrances. The largest tomb in Japan dates back to the Kofun period and is the tomb of Emperor Nintoku; it has forty-six burial mounds.

Another interesting discovery in Japan, dating back to the Kofun period, is a bronze mirror, likely made by the Yayoi people.

Asuka and Nara Art

The Asuka and Nara periods, named because the seat of the Japanese government was located in the Asuka Valley from 542 to 645 AD and then in the city of Nara until 784 AD, were a very important time for art in the country due to the spread of Buddhism from China.

There is controversy regarding the dates of this period, but it is normally categorised into three periods: the Suiko period (552-645 AD), the Hakuhō period (645-710 AD), and the Tenpyō period (710 - 784 AD). During this timeframe, Buddhism was introduced to Japan and influenced not just the art but the entire culture of the country.

Buddhist art came to Japan with various immigrants, and the oldest known sculptures of the Buddha date back to the 6th and 7th centuries. From this period onwards, there are various sculptures of the Buddha found in Japan designed with Chinese influences.

There are wooden buildings in Japan that date back to the early 7th century. One of the most famous ones found in Hōryū-ji is a complex of forty-one buildings, including the Kondō (Golden Hall) and Goju-no-to (the five-storey pagoda), which are the most important.

The Kondō is built in the style of a Chinese Buddhist worship hall and houses some of the most significant sculptures of the period, known as the Shaka trinity. The Shaka Trinity is a Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas cast in bronze, made by the sculptor Tori Busshi in the 7th century in honour of the deceased prince Shōtuku.

At the four corners of the platforms where the Shaka Trinity is displayed, carved in wood are the Guardian Kings of the Four Directions. Hōryū-Ji also houses the Tamamushi shrine, which is a miniature wooden replica of the Kondō that is decorated with figural paintings.

Metal engraving and sculpting, known as Choukin, started during the Nara period.

Heian art

The time known as the Heian period began in Japan when the capital moved to Heian-kyō (now known as Kyoto) in 794 AD and lasted until 1185 AD. The Kamakura Shōgunate was established during this period preceding the Genpei War.

One major change to Japanese art came when priest Kūkai, also known posthumously as Kōbō Daishi, travelled to China and studied Shingon, a form of Vajrayana Buddhism which was subsequently spread in Japan in 806 AD. Shingon centres around the mandalas, which are believed to be maps of the spiritual universe, and this influenced the design of Japanese temples.

Japanese Buddhist architecture also adopted the Stupa, once an Indian design but adopted by the Chinese for use in their pagodas. Shingon temples were built high in the mountains away from city life and used indigenous materials like cypress bark for the roofs and wooden planks for the floors instead of ceramic tiles and earthen floors.

The practitioners of Shingon were deeply spiritual and saw themselves as apart from commoners, for whom they built separate prayer halls away from the main sanctuaries.

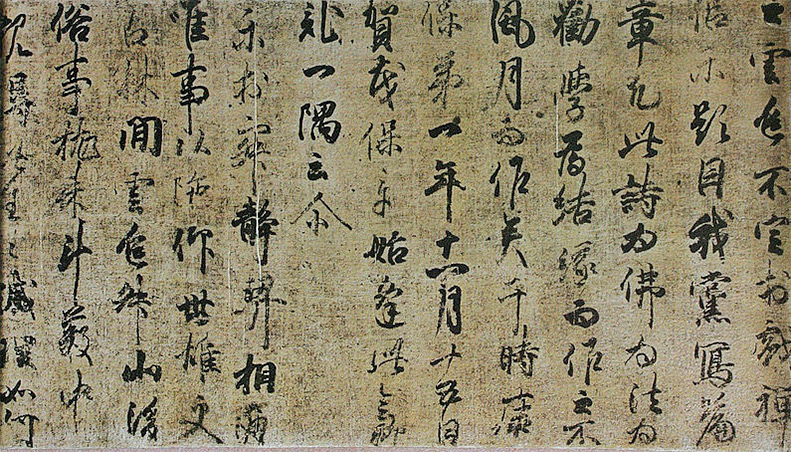

An interesting artistic concept developed towards the end of the Heian period, known as Emakimono, or emaki, which were horizontal, painted scrolls. Emaki were illustrated stories, the most famous of which is known as the Tale of Gengi or Genji Monogatari Emaki, which is a story of romance and court intrigue and is the oldest surviving Yamato-e hand scroll written in 1000 AD by the novelist, Murasaki Shikibu.

Two separate styles of painting emerged from the emaki known as Otoko-e (men’s pictures) and Onna-e (women’s pictures), in which the subject and painting style appealed to both genders cognitively and aesthetically. Whilst the Otoko-e generally contained historical events like battles, the Onna-e was filled with love and romance like the Tale of Genji.

The art of Origami was also an important part of Japanese culture during the Heian era.

Fujiwara Art

During the Fujiwara period, a different form of Buddhism known as pure land Buddhism became popular among the ruling elite, like the Fujiwara family, who ruled as regents for the Emperor and who the period was named after.

Unlike the isolated Shingon mountain temples, the temples dedicated to pure land Buddhism resembled the houses of the rich and contained the Amida hall, in which the images of the Buddha were displayed.

Kamakura Art

After the five-year-long war (known as the Genpei war) between the Taira and Minamoto clans from 1180 to 1185 AD, the Minamoto seized power and established a government in the village of Kamakura, resulting in a power transfer from nobility to the warrior class. This meant that art that was produced to please the elite class now had to appeal to men of war, whose outlook on life was completely different. The art of the Kamakura period was based on realism and contemporary designs to meet the interests of the new rulers.

Phenomenal sculptures were made during the Kamakura period, including the two Niō guardian images in Nara and the polychrome wood sculptures of the Indian sages, Muchaku and Seshin, who founded the Hussō sect.

A very interesting artistic discovery was made in the Kegon Engi Emaki, which is the illustrated history of the Kegon sect. The sect lost popularity due to the rise of the Pure Land sect, but following the Genpei war, the monk Myōe of Kōzan-ji provided a refuge for the widows of the fallen warriors. Wives of the Samurai were only taught basic reading skills and were discouraged from learning more complex forms like kanji; thus, the Kegon Engi Emaki is a combination of pictures and simple texts written next to the characters as dialogue, making it the precursor to the modern comic strip.

Muromachi Art

In 1338 AD, the Ashikaga clan took the reins of power from the Samurai and returned it to the elite, where they moved the government back to the Muromachi district in Kyoto and introduced Zen Buddhism. The art style was rapidly changed, and the once colourful, realistic paintings of the Kamakura period were replaced with minimalistic black and white paintings in the Chinese manner.

The most popular 15th-century paintings of this period include the depiction of the monk Kensu by priest-painter Kao, “Catching a Catfish with a Gourd” by priest Josetsu, “Reading in a Bamboo Grove” by Tenshō Shūbun and “Landscape of the Four Seasons” by Sesshū Tōyō in 1486, who travelled to China to learn Chinese painting at its birthplace.

The Muromachi period ended in 1573 when the Samurai regained control after 100 years of war.

Azuchi Momoyama Art

In 1573, Oda Nobunaga removed the last Ashikaga Shōgun and was succeeded by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, along with Tokugawa Ieyasu of the powerful Tokugawa clan, who stepped in and established a Shōgunate that would last from 1603 to 1867.

The bright style of painting loved by the Samurai returned, and a new artistic trend emerged, developed by Kanō Eitoku, the design concept of having a painted landscape on the sliding doors of a room. Screen paintings also became popular, allowing the painter to have a much longer platform to work with.

Edo Art

The Tokugawa Shōgunate brought political stability to Japan after centuries of warring clans fighting for control. Under the Tokugawa, Japan was closed to all foreigners in an attempt to preserve culture and prevent the adulteration of Japanese culture from mainland Asia.

During this period, circuit-style Japanese gardens were made, and daimyōs (clan leaders) competed in terms of the beauty of the gardens.

The reproduction of texts and images was done through woodblock printing; the method of woodblock printing involves engraving an image on wood and stamping it on a piece of paper.

The painter Sōtatsu produced one of the most famous Japanese screen paintings, “The Waves at Matsushima”, and a century later, in the same style, Kōrin painted the “Red and White Plum Blossoms.”

The 19th-century painters Hokusai and Hiroshige are well known for their landscape prints, and they influenced many Western artists and poets.

Two distinct art forms developed during this period as a result of the country’s politics: Ukiyo-e, which depicted life outside the bounds of the Tokugawa Shōgunate and Nanga, which focused on Chinese, meaning a foreign style of painting, clashing with government policies.

As a result of the Japanese invasions of Korea in the 1590s, many Korean potters were captured who then taught the Japanese how to make the Chinese-style chambered climbing kiln, which was more efficient as it allowed high temperatures with better control, and these were called noborigama.

The discovery of a deposit of kaolinite in 1620 led to the production of porcelain in Japan. Although the Tokugawa Shōgunate isolated the country from foreign influences, restricted trading was permitted in the port of Nagasaki, allowing a certain degree of foreign influence over art in that particular region.

In the 1650s, the collapse of the Chinese porcelain industry due to civil war meant that Japan was the prime exporter of porcelain in the region, and they exported large amounts to Europe and the Islamic world. Lacquerware also became popular among merchants and the Samurai class.

Pre-War Art - Meiji Period

In 1868, the Emperor of Japan regained ruling power over the country and lifted the isolation imposed by the Tokugawa Samurai rulers. This change brought a new wave of foreign, particularly Western, influences to the art and culture of the country.

Based on European models, innovative designs of architecture and gardens became apparent, such as the Tokyo train station and the National Diet Building, which were constructed using bricks and resembled Western buildings.

Manga cartoons were also published during this period based on English and French political cartoons.

In 1876, the Technological Art School was opened and had Italian instructors to teach the Japanese Western art forms and painting. With the new influx of ideas from the West, Okakura Kakuzō led a movement to encourage Japanese artists to preserve their traditional forms of artistic theory known as Yōga (Western-style painting) and Nihonga (Japanese-style painting).

With new technology to experiment with, spectacular enamels were produced in Japan during the Meiji period, and the years from 1890 to 1910 were known as the golden age for Japanese enamels.

The new firing process allowed larger blocks of enamel to be produced with fewer cloisons, making it the perfect medium for painting on. The enamels featured paintings of flowers, birds, and insects, as well as reproductions of traditional paintings, and this style was unique to Japan.

Top enamel artists at the time were Namikawa Yasuki and Namikawa Sōsuke, who won many awards. Lacquerware also became popular, and Japanese lacquer products were regarded as the best in the world.

During this period, porcelain, earthenware and textiles reached new heights of quality and popularity. Japanese experience with creating weapons and armour for the Samurai enabled them to produce exquisite metalwork since the materials could now be imported, paving the way to an even further advancement in Japanese art techniques.